The evolution of prosthetics has been one of the most remarkable journeys in medical science, combining technological advancements with a deep understanding of human anatomy. From the earliest wooden limbs of antiquity to the sophisticated artificial limbs of today, prosthetics have continuously evolved to better serve individuals who have lost limbs due to trauma, disease, or congenital conditions. However, as technology advances at an unprecedented rate, the question arises: is the future of prosthetics fully bionic?

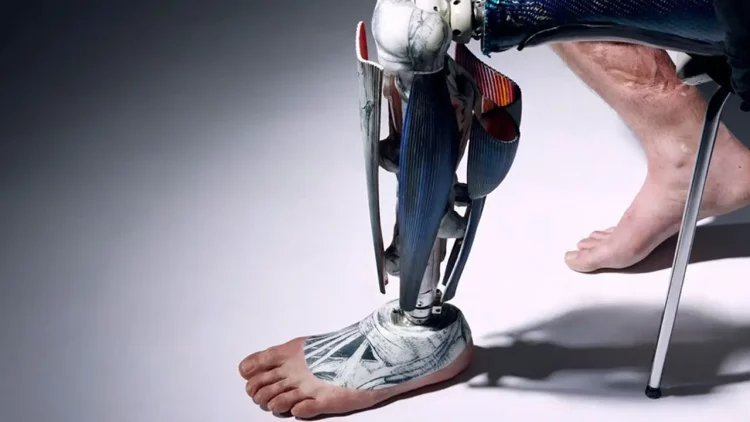

To understand where prosthetics are heading, it is important to first explore the current state of the field. Prosthetics today range from traditional mechanical limbs to more advanced designs incorporating robotics, artificial intelligence (AI), and cutting-edge materials like carbon fiber and 3D-printed components. These innovations offer increased functionality, comfort, and, most importantly, a semblance of natural movement. However, the ultimate goal of “fully bionic” prosthetics—artificial limbs that not only replicate the function of natural limbs but also mimic their biological characteristics in ways that blend seamlessly with the body—remains elusive.

In this article, we will dive into the current state of prosthetics, the advances being made toward fully bionic systems, the challenges that remain, and what the future holds for individuals who rely on prosthetics for mobility and functionality.

The Evolution of Prosthetics: From Simple to Complex

Prosthetics have come a long way from their humble beginnings. In ancient Egypt, prosthetics were rudimentary: a simple wooden or metal toe, for example, designed to help the user walk. These early prosthetics, while functional, lacked both comfort and mobility, as they were purely mechanical and had no way of interacting with the body’s biological systems.

Fast forward to the 20th century, and prosthetic limbs began to incorporate more advanced materials, such as lightweight plastics and metals, and systems that allowed for better joint movement. However, it wasn’t until the late 20th and early 21st centuries that prosthetics began to closely resemble the complex, functional limbs that we see in the modern era.

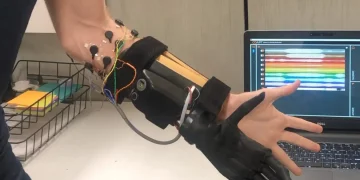

The introduction of myoelectric prosthetics in the 1950s was a game-changer. These devices use electrical signals from the user’s remaining muscles to control the movements of the prosthetic. This technology represented a major leap forward, allowing for more precise and dynamic limb control. But it also exposed the limitations of current prosthetics: although they could mimic some motions of natural limbs, they still lacked the fluidity, versatility, and sensitivity of biological arms and legs.

Today’s prosthetics often go beyond simple mechanical design to include technologies like sensors, actuators, and advanced control systems that can mimic human movements more accurately. Still, most of these systems are far from fully bionic—meaning they don’t yet offer the full range of sensation, dexterity, or adaptability that a biological limb would provide.

The Quest for Fully Bionic Prosthetics

The term “bionic” is often used to describe prosthetic limbs that closely mimic the functionality and appearance of natural limbs. However, achieving a truly bionic limb means much more than just building a limb that looks like a human arm or leg. A fully bionic prosthetic would need to replicate not just the physical movement of a biological limb, but also integrate seamlessly with the user’s nervous system, offering sensory feedback, fine motor control, and adaptability to the environment.

Mimicking Biological Movement

One of the first and most important aspects of a bionic limb is the ability to move fluidly, just like a biological limb. Traditional prosthetics rely on basic mechanical movements, often using joints, springs, and rods. Myoelectric prosthetics, on the other hand, use electrical signals from the muscles to control the movements of the limb. These technologies can enable prosthetics to perform more complex tasks, such as gripping and twisting, but they are still limited in their ability to offer natural motion.

True bionic limbs would need to incorporate more advanced technologies, such as artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning, to allow them to learn and adapt to the user’s specific movements and habits over time. For instance, a bionic arm could adjust its grip strength based on the object being held, or a bionic leg could adapt to walking on uneven surfaces. This kind of dynamic, real-time adjustment is one of the hallmarks of human movement, and achieving it in a prosthetic limb is one of the biggest hurdles on the path to a fully bionic future.

Sensory Feedback: The Missing Piece

While current prosthetics can provide some basic movement, they are lacking in sensory feedback—the ability to feel touch, pressure, temperature, or pain. For example, a person using a prosthetic hand might be able to move the fingers, but they would have no way of feeling whether they were holding something too tightly or whether the surface of an object was rough or smooth.

Researchers are actively working on developing technologies that can provide sensory feedback to prosthetic users. Some experimental systems use sensors in the prosthetic limb to detect pressure or touch and send signals to the user’s nerves, creating a sense of sensation. One promising area of research involves using nerve interfaces, where electrodes are implanted in the residual limb’s nerves to transmit sensory information directly to the brain. While still in the experimental stage, this type of sensory feedback could revolutionize the way users interact with their prosthetics and their environment.

Neurological Integration

In addition to providing sensory feedback, a fully bionic prosthetic would need to seamlessly integrate with the user’s nervous system. This means that the brain would need to be able to “talk” to the prosthetic in much the same way it communicates with natural limbs. Currently, prosthetics use signals from the muscles or the brain to control movement, but this system is still far from perfect. For a bionic prosthetic to truly mimic a natural limb, the communication between the brain and the prosthetic must be almost instantaneous, with the prosthetic responding to the user’s thoughts and intentions in real-time.

Researchers are exploring various methods of neurological integration, including brain-computer interfaces (BCIs) and direct neural interfaces. These technologies involve placing electrodes on or within the brain to detect neural activity, which is then translated into commands for the prosthetic limb. This technology is still in the early stages but shows promise for creating truly intuitive, bionic limbs that respond to thought.

Challenges on the Path to Fully Bionic Prosthetics

Despite the tremendous advancements made in prosthetics, there are still significant challenges that must be overcome before fully bionic limbs can become a reality.

Cost and Accessibility

One of the biggest challenges facing the development of fully bionic prosthetics is the cost. The technologies required to create prosthetics that are fully integrated with the nervous system, provide sensory feedback, and adapt to the user’s movements are expensive. At present, the cost of even the most advanced prosthetic limbs can be prohibitively high, often putting them out of reach for many people who could benefit from them.

Moreover, the ongoing need for maintenance, repairs, and upgrades means that the long-term cost of owning a bionic prosthetic can be substantial. To make these prosthetics more widely available, researchers and companies must work to drive down costs through technological advances, manufacturing efficiencies, and greater competition in the marketplace.

Biocompatibility

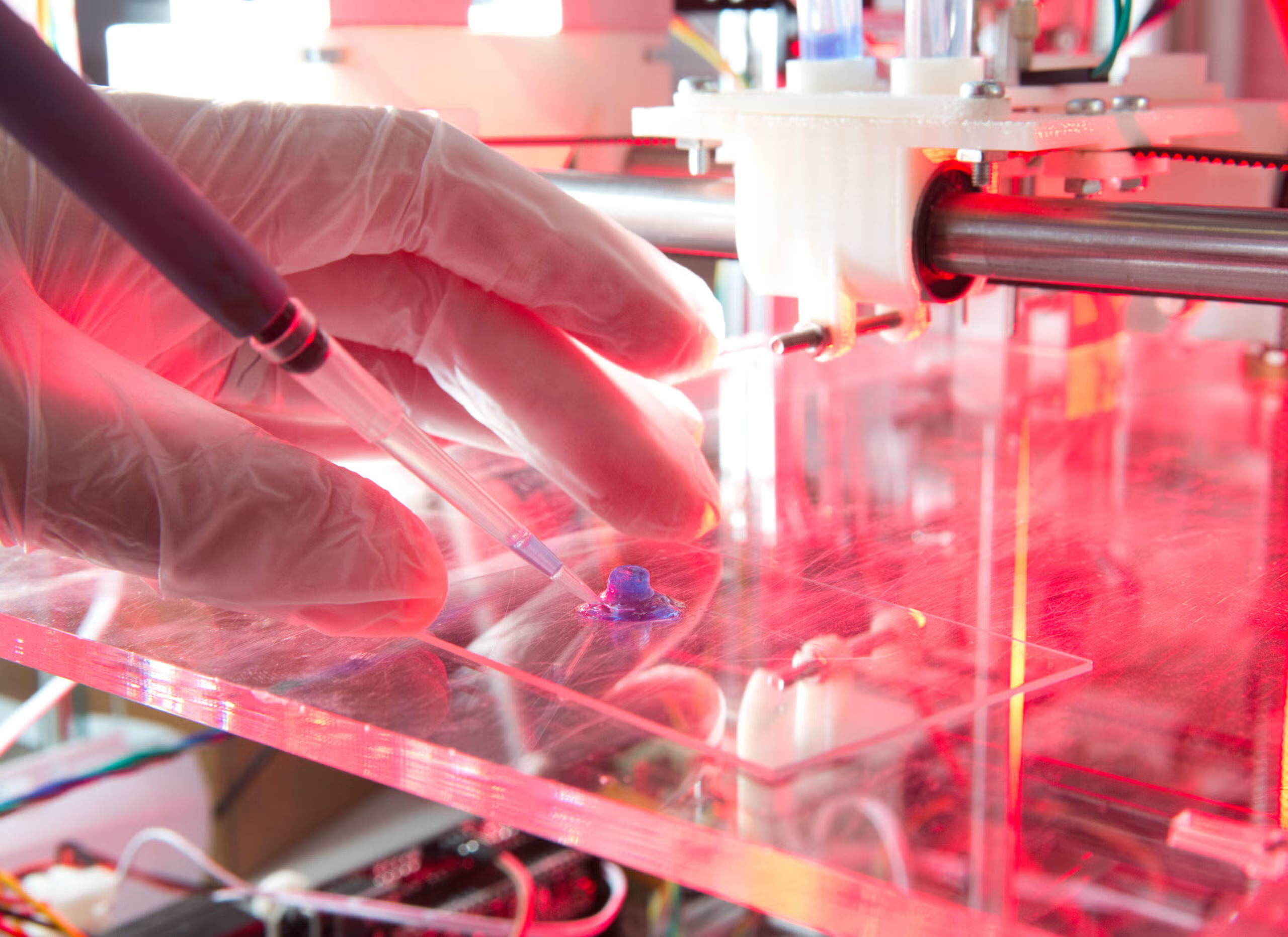

Another significant hurdle is ensuring that bionic prosthetics are biocompatible. This means that the materials used in the prosthetic must not only be durable and functional but also safe to use with the human body. For example, the prosthetic must be able to interact with the skin, muscles, and nerves without causing irritation or damage.

The interface between the prosthetic and the user’s body is critical, as it determines how well the prosthetic can function over time. Research is ongoing to develop better skin-like materials that can mimic the flexibility and sensation of human skin, as well as better electrode interfaces for communicating with nerves.

Ethical and Psychological Implications

As prosthetics become more advanced, ethical and psychological questions also arise. For instance, the line between medical devices and augmentation may begin to blur as prosthetics become more capable. Should individuals with prosthetic limbs be given access to technology that enhances their capabilities beyond what is normal for the human body? Additionally, the psychological impact of using a bionic limb is complex; for some, the transition to using a prosthetic can be empowering, while for others, it can be a difficult adjustment.

As prosthetics continue to improve, these issues will become more pronounced and may require careful consideration and regulation.

What’s Next for Prosthetics?

The future of prosthetics is undeniably exciting, with significant advancements being made in the areas of robotics, neuroscience, and material science. However, the path to fully bionic prosthetics is still in its early stages, and there are many challenges that remain.

In the coming years, we can expect to see prosthetics that are more affordable, comfortable, and functional, with greater integration with the human body. These advancements could lead to prosthetics that not only allow for more natural movement and better sensory feedback but also offer greater independence and quality of life for individuals with limb loss.

Ultimately, the question of whether the future of prosthetics is fully bionic remains open. While we are undoubtedly making strides in that direction, the journey is still ongoing. As technology continues to advance, it is clear that prosthetics will become an increasingly important part of the human experience, offering not just restoration of lost function but also new possibilities for enhancing human abilities.